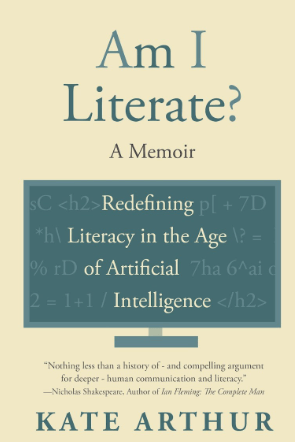

Excerpt from my book, Am I Literate? Redefining Literacy in the Age of AI

Literacy means more than knowing how to read and write; it is an understanding of how we interact with the world around us and our active role in shaping it. It is how we share with others—how we express our experiences, hopes and dreams, and how we understand what is shared with us in return. Literacy connects us with others, nature, machines, and ourselves. It is the way we create information and the way we decipher it. Literacy becomes meaningful when society recognises, values, and adopts the communication tools and channels to share the knowledge. It is also a term with many definitions, means different things to different people, and evolves with context.

In this book, literacy is defined as the valued and socially accepted skills, knowledge, and tools necessary to create, communicate, and understand information. We are ‘literate’ when we can access data, transform it into knowledge, and respond meaningfully—all within the material and social frameworks that enable connection. Literacy, in this sense, is not static; it evolves with society’s needs, channels, and technologies.

The history of literacy reflects the progression of human communication, knowledge sharing, and cultural development for civilisations all around the world. From early pictograms to social media, these systems have shaped societies and expanded our capacity for learning and expression.

Before the 15th century, mass communication was largely verbal, supported by limited written and visual aids. The ability to read and write was primarily confined to those in power or those who worked for them. Only a select few knew how to craft a message, decipher it, and respond effectively. Between the 11th and 13th centuries in England, writing began to rise as a dominant tool for organising and recording information, particularly within society’s economic, religious, and political frameworks.

The purpose of literacy was not just to document information but also used as an impetus for dominance over the masses. For example, in the 11th century, Norman invaders in Europe relied on writing to “assert the authority of the central government, beginning with an ambitious census of their new territory, and [to] create a new bureaucracy.” This was, and still is, a form of control; holding the reins of literacy has long been a powerful tool for those seeking to maintain dominance and influence over a society. An individual’s access to literacy was dictated by their social class and status, and those without status were often prohibited from learning to read and write altogether.

Throughout the Middle Ages, from 11th to 15th century, education included the practice of legere (reading to properly pronounce text) and intellegere (understanding through grammar and vocabulary). While children often learned basic reading at home, full comprehension was available in grammar schools, which was accessible only to boys. Girls—commonly excluded from grammar education—missed the chance to learn writing, a study which centred on Latin and was typically taught through copying the Latin alphabet and Latin words. By 1500, only about 1% of women in England were literate. The expansion of colonial and imperial forces—driven by male-centred Anglo-European ideologies from the 15th century onward—established global power structures that continue to shape the world today.

The term ‘literate’ originated in the early 15th century as an adjective denoting someone who was educated, instructed, or possessed knowledge of letters. During the same period, ‘illiterate,’ meaning ‘unlearned, unlettered, ignorant, without culture, inelegant,’ described those who lacked education and the inability to read and write. Centuries later, being literate was also associated with being ‘acquainted with literature.’

Literacy enabled the centralisation of control and the exercise of power. Being literate extended beyond reading and writing to include arithmetic, an essential skill for governance, trade, and taxation. Mastery of these three skills —alluded to in St Augustine’s Confessions in Latin as ‘legere et scribere et numerare discitur (learning to read, and write, and do arithmetic)’, and much later in the 19th century, coined as the ‘3 Rs’ or reading, writing, and arithmetic by British politician Sir William Curtis—were markers of an education and a ladder for social stratification.

The invention of the modern printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in 1439 helped integrate the written form of communication into society. The printing press and Venice’s extensive shipping network enabled the first mass distribution of printed materials. They allowed for rapid, inexpensive, large-scale production, establishing a rudimentary global news network that reached broad audiences. Ships carried religious texts, pamphlets, and the latest news from around the world to distant ports, where local printers made copies and handed them to riders for inland distribution. Despite low global literacy rates in the 1490s, locals gathered in public spaces to hear paid readers share the latest news—from sensational scandals to war updates. As historian Ada Palmer notes, “This radically changed the news consumption…It made it normal to go check the news every day.” The written word started to connect communities and countries, and those who were literate were able to record information into history, whether true or not.

Written documents also contributed to the creation of infrastructures—such as libraries and schools—spaces that protect the collective memory and nurture intellectual growth. These institutions allow for the preservation and dissemination of ideas, encouraging cultural exchange, and are symbols for the value that we place on knowledge. During the Enlightenment period (1685–1815), literacy education—specifically the 3 Rs—was seen as essential for all. Schools began to implement these foundational skills, recognising their importance for civic participation and economic productivity—though without an urgency of an industrial revolution where mass training was needed, the widespread integration was slow.

In the 1880’s, the term ‘literacy’ was first recorded, originating from the word ‘literate’, and referring to someone’s ability to read and write. And while the privileged were being educated to be literate, there were those who were not: the illiterate. Those who were illiterate faced negative social and economic consequences, which created barriers to participating fully in society and engaging with its resources and opportunities.

The First Industrial Revolution (1760–1840) took full hold in Europe in the mid-18th century, driving the need to up-skill the workforce and educate youth in the 3 Rs. Although it was a highly disruptive period, the displacement of workers due to new inventions was not unprecedented. Before Gutenberg’s invention, scribes were in high demand, as bookmakers relied on skilled artisans to hand-copy and decorate manuscripts. By the late 15th century, the printing press had nearly eliminated the need for their skills. However, the surge in printed materials created a new industry, including printers, booksellers, and street vendors. Jobs disappeared, and new ones were created—a cycle that repeats with every wave of innovation.

As information consumption spread, governments and religious institutions seized the opportunity to use printed materials to manipulate and control public opinion. With the dissemination of information came misinformation, disinformation, and propaganda. The reproduction and distribution of written material increased significantly, as did the impact, and reach of false and inaccurate information. Throughout the 1800s, newspapers appeared across the globe, contributing to literacy growth while also helping the widespread circulation of false news.

Although false news was not new—Octavian’s campaign to smear Mark Antony’s reputation dates to 44 BC—the printing press amplified it. Quite rapidly, there were extraordinary stories of sea monsters and witches being blamed for natural disasters, and even an alien civilisation discovered on the moon, or so the sensational headlines in New York’s paper would lead people to believe. As it came to be known, the Great Moon Hoax of 1835 promoted the Sun to become a leading, profitable newspaper. Fake news made—and still makes—lots of money. Without objective fact-checking, rumours easily evolved into accepted facts and eventually official news. Over time, however, people began to rebel against fake news. They sought objective sources, which led to the rise of journalism and its establishment as an industry.

Communication tools and methods of connecting have changed throughout history, and humans have always been drawn to the astonishing and extreme to ignite passions, fuel prejudices, and provoke reactions. As long as humans are involved, the temptation to manipulate audiences will persist. Therefore, the responsibility to protect citizens from false news must not disappear.

Today, literacy is recognised as an empowering, liberating force. It opens up opportunities, reduces poverty, enhances labour market participation, and positively impacts health and sustainable development. As the responsibility of the United Nations—more specifically, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO)—education and literacy are a priority for sustainable development and global citizenship. In 2005, UNESCO released Education for All: Literacy for Life, defining literacy as “identification, understanding, interpretation, creating, and communication in an increasingly digital, text-mediated, information-rich and fast-changing world.”

Literacy is more than just a skill: it requires access to tools and the integration of those tools into society—whether paper and pens, or keyboard and a computer. Literacy enables individuals to take personal and social responsibility by applying knowledge, both learned through education and gained through experiences, and empowering them to engage actively in their communities and broader society. Literacy involves employing critical and creative thinking, communicating ideas through various methods, and using knowledge and skills to interpret and connect diverse contexts—knowledge, skills and tools that should be accessible to everyone.

A literate society is recognised as essential for economic growth, and as a result, society grew to value education. In Europe, during the First and Second Industrial Revolutions, education opportunities first opened to boys, and over time, included girls. In part it was the minority of women who had access to education that fought for girls’ rights to go to school. Our communities have come to benefit from women’s education. Literacy enables families to access information, communicate effectively, and participate in social, economic, and political activities. Women empowered by literacy create a positive ripple effect on individual and societal advancement; it provides women with broader life choices and directly impacts their families’ well-being, significantly enhancing the education of female children.

In the early 1800s, only one in ten people globally could read and write. In 2024, 95% of the global population has basic literacy skills. However, significant gaps remain, particularly in impoverished regions such as sub-Saharan Africa, where fewer than one in three adults are considered to be literate—despite 200 years having passed since literacy was recognised as an essential component of education, and 50 years since the United Nations introduced International Literacy Day in 1967. Today, over 750 million people still lack basic literacy skills. Millions of children struggle to achieve minimum proficiency in reading, writing, and numeracy, and approximately 250 million children remain out of school. Although substantial progress has been made, closing the gap remains an ongoing challenge, especially as the digital divide adds further pressure on literacy development.

For more: Am I Literate? Redefining Literacy in the Age of Artificial Intelligence

Sources

Vee, Annette. 2017. Coding Literacy. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Norman, Jeremy. 2024. “The Growth of Literacy from 1100 to 1500.” History of Information. http://www.historyofinformation.com.

“Literacy is More than Just Reading and Writing.” 2020. National Council of Teachers of English. ncte.org/blog/2020/03/literacy-just-reading-

writing

Merriam-Webster Dictionary. 2024. “Illiterate.” Merriam-Webster Dictionary. http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/illiterate.

Ryan, John K., ed. 1960. The Confessions of Saint Augustine. Translated by John K. Ryan. N.p.: Random House Publishing Group.

Dictionary.com. n.d. “Three R’s.” Dictionary.com. https://www.dictionary.com/browse/three-rs.

Roos, Dave. 2019. 7 Ways the Printing Press Changed the World | HISTORY. http://www.history.com/news/printing-press-renaissance.

Editors, History.com. 2009. Enlightenment Period: Thinkers & Ideas | HISTORY. http://www.history.com/topics/european-history/enlightenment.

Online Etymology Dictionary. 2018. “Illiterate.” Online Etymology Dictionary. http://www.etymonline.com/word/illiterate.

“The Propaganda of Octavian and Mark Antony’s Civil War.” 2019. World History Encyclopedia. http://www.worldhistory.org/article/1474/the-propaganda-

of-octavian-and-mark-antonys-civil.

Matthias, M. “The Great Moon Hoax of 1835 Was Sci-Fi Passed Off as News.” Encyclopedia Britannica, July 22, 2021. http://www.britannica.com/story/the-great-moon-hoax-of-1835-was-sci-fi-passed-off-as-news.

SOLL Sitrin, Bill Mahoney, and Josh Gerstein. 2016. “The Long and Brutal History of Fake News.” Politico. http://www.politico.com/magazine/story/

2016/12/fake-news-history-long-violent-214535/.

UNESCO. 2024. “Literacy: what you need to know.” UNESCO. http://www.unesco.org/en/literacy/need-know.

UNESCO. 2024. “Literacy: what you need to know.” UNESCO. http://www.unesco.org/en/literacy/need-know.

Roser, Max, and Esteban Ortiz. n.d. “Literacy.” Our World in Data. Accessed November 24, 2024. ourworldindata.org/literacy.

World Population Review. 2024. “Literacy Rate by Country 2024.” World Population Review. worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/literacy-

rate-by-country.

UNESCO. 2024. “251M children and youth still out of school, despite decades of progress.” UNESCO. http://www.unesco.org/en/articles/251m-

children-and-youth-still-out-school-despite-decades-progress-unesco-

report.

Leave a comment